The Stranger-Danger Bias

Airbnb is an online marketplace for people to lease or rent short-term lodging, and to create or book local experiences. It has disrupted the hospitality industry and convinced millions of people to do something that was previously unthinkable: sleeping in a stranger’s home.

Airbnb is one of key players in the “platform revolution”: A revolution of fast-growing tech companies whose success depends on the careful orchestration of high-value interactions among users.

Airbnb prides itself on embracing a user-centred approach to design and innovation. As the co-founders put it, Airbnb "bleeds design”.

Airbnb "bleeds design”

According to his co-founder Joe Gebbia, the number one secret for Airbnb’s success has been their ability to tackle the stranger = danger bias.

Most people are risk averse and sleeping at a stranger’s home activates our inner fears of the “unknown other”. In other words, they have identified the key barrier that all sharing economy companies face - lack of trust - broken it down in its components, and designed for it.

Two design interventions, co-founder of Airbnb Joe Gebbia explains, have helped overcome mistrust early on.

The first is a solid reputation system.

Since we prefer people that are like us, our willingness to trust someone increases as the similarity (eg., age, location) increases. What happens when reputation is added to the mix?

An early study in collaboration with Stanford found that if a host has 1-3 reviews nothing happens. But when a host has more than 10, everything changes: high reputation beats high similarity. As Joe Gebbia puts it: “The right design can actually help us overcome one of our most deeply rooted biases”.

The right design can actually help us overcome one of our most deeply rooted biases”.

The second thing they learned is that building the right amount of trust takes the right amount of disclosure.

Sharing too little or too much decreases acceptance rate from hosts. That’s why Airbnb uses the size of the box to suggest the right length and guide users with prompts to encourage sharing.

Creating trust was the first step in Airbnb’s behavioural design. Since then, much more can be learned from the way Airbnb onboards, converts and engages its guests.

A quick Make it audit reveals 6 core behavioural strategies and many related tactics.

Make it scarce

Arguably scarcity permeates Airbnb’s core value proposition of finding “unique homes” across the globe, from tree houses to historical homes (Scarcity as uniqueness and authenticity). This is in contrast with standardised hotel rooms and residences offered by hotel chains. Availability is also made explicit through clever and timely copy along the user journey.

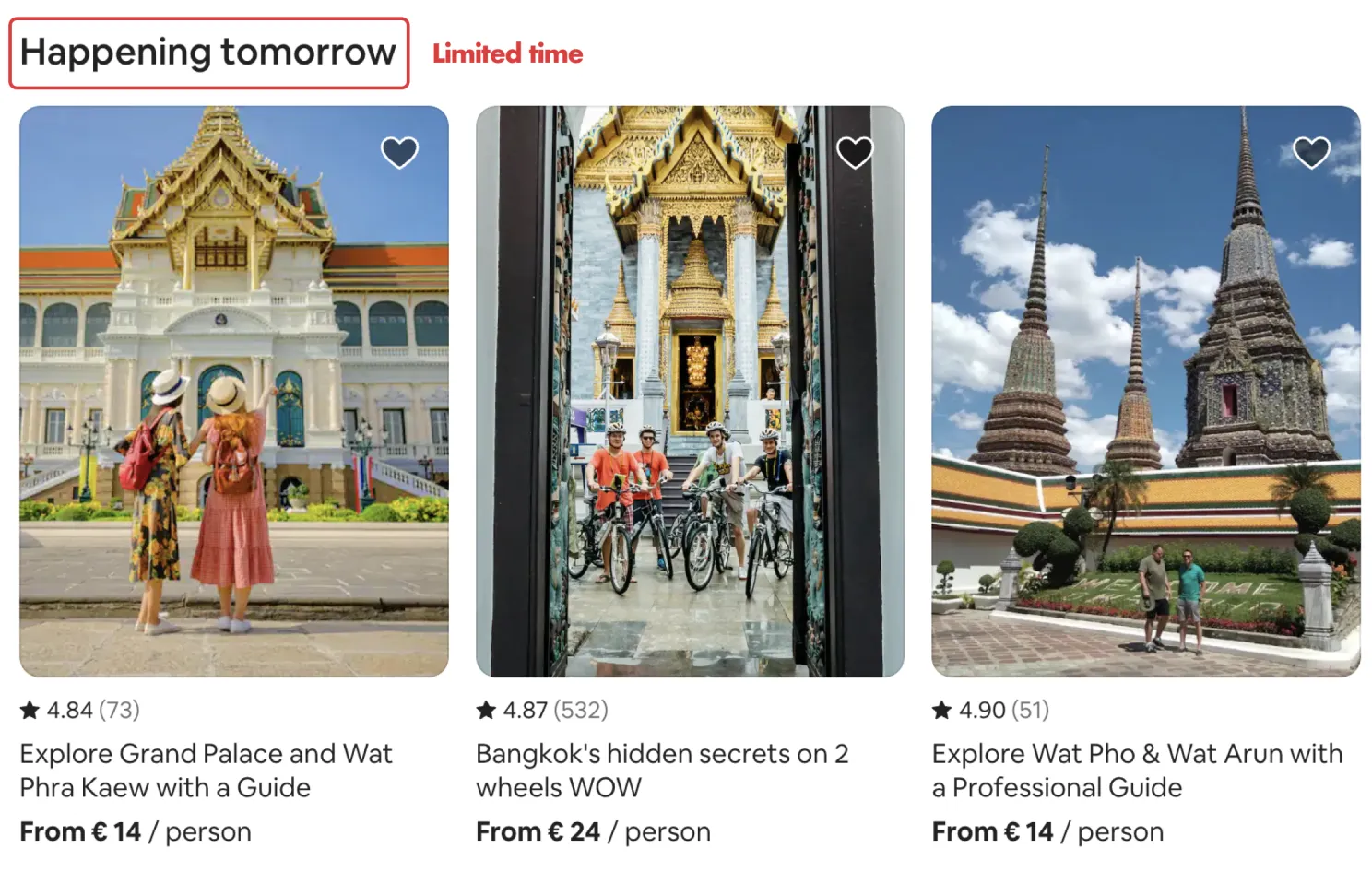

Scarcity cues include information about Limited Resources, by highlighting the number of available listings left in the dates a user is searching (“only 8% of listings are left for these dates”; Limited Time, to take action (“book soon to get this special offer”, "Happening tomorrow") and Rarity, by signalling when a user finds an accommodation that is usually booked (“this is a rare find”).

Scarcity cues include information about Limited Resources, by highlighting the number of available listings left in the dates a user is searching (“only 8% of listings are left for these dates”; Limited Time, to take action (“book soon to get this special offer”, "Happening tomorrow") and Rarity, by signalling when a user finds accommodation an accommodation that is usually booked (“this is a rare find”).

In marketplaces like Airbnb (ecosystems having a supply and demand side), scarcity is closely related to two other behavioural strategies. First, scarcity triggers an aversive response, which creates a sense of urgency to complete a booking (“book before it’s gone”). And secondly, it operates in synergy with a social strategy, since the availability and rarity are highly dependent on the (unpredictable) choices of other guests (you never know when a listing will be booked by another guest).

But Airbnb has not stopped its social strategy there.

Make it social

To help users make the right choice, Airbnb leverages social proof, by recommending top viewed and wish-listed listings, best-selling experiences, and most importantly, thanks to a strong rating and review system.

Social proof is nothing new in the e-commerce space. However, unlike most services, Airbnb uses machine learning to generate insights from user reviews and show them in a dedicated (and obvious) “home highlights” section on top of the listing page.

Perhaps less explicitly, Airbnb also leverages our desire to be special, communicated with the slogan “experience a city like a local”. At Airbnb you are a traveller, not a tourist.

At Airbnb you are a traveller, not a tourist.

This approach is in sharp contrast with other brands which have mostly focused on monetary incentives (in the form of great deals and traditional point-based loyalty programs).

Two more behavioural dynamics are crucial for Airbnb social interactions: cooperation and reciprocity among guests and between guests and hosts.

First, it has attempted to turn travel planning into a group experience through a Collaborative Wishlist feature. which makes it easier for friends travelling in a group to find a rental everyone can agree on.

The second tactic in action is reciprocity, the human universal tendency to be much nicer and much more cooperative in response to friendly actions. Reciprocity explains our obligation to say thank you to return a nice gesture, and exchange favours (as well as retaliate in reaction to a harmful action).

By regulating players' behaviour and promoting cooperation, reciprocity plays a crucial role in creating a thriving ecosystem at Airbnb (and similar platforms).

However, reciprocity doesn’t always lead to a desirable outcome when taking an ecosystem perspective, and it has important implications in the design of reputation systems.

Airbnb has a two-sided system, meaning that the guest and the host each have the opportunity to review one another. Obviously it’s in the interest of both parties to have a high score: if a host has low ratings, he’ll receive fewer bookings, and if a guest has low score, he’ll have a hard time to be accepted by future hosts.

Before 2014, both reviews were published as soon as they were written. This means that the second reviewer (either the host or the guest) could be influenced by what the first reviewer said, rather than the actual experience.

Reciprocity would beat honesty.

This led Airbnb to a redesign.

The reviews are now hidden until both parties have reviewed or until the time to review (14 days) has expired. After reviews are revealed, they cannot be modified, which makes it impossible for users to retaliate against a negative review, or based their positive review purely on our need to reciprocate (we’ll discuss another important behavioural element of this in Part 2 of this article).

Another related social psychology principle to keep in mind when designing interactions, is liking: our tendency to say ‘Yes’ to requests of someone we like. Liking (more about it here) is often related to our bias towards our “tribe” (similarity). As discussed above, in the case of Airbnb it was a barrier to trust strangers (people we find difficult to like). This may explain why you’d be more keen to choose a host that has similar hobbies to yours. But we also like people that give us compliments, are willing to cooperate, and that trigger positive association (among other means).

The principles of scarcity and social influence are the pillars of Airbnb’s communication and product innovation strategy. Enter Make it Meaningful.

Make it meaningful

AAs Simon Sinek (author of Start with Why) beautifully puts it: “People don't buy what you do, but why you do it!. Brands with a truly loyal customer base know how to shape and communicate effectively their brand conviction: their purpose and meaning, beyond mere profit.

While creating a meaning and purpose strategy is never done overnight, Airbnb has done a great job not only at communicating what they believe in, but also at building products and features to enable users to take action in line with those values.

1. Find and communicate your purpose:

Leigh Gallagher explains in The Airbnb Story (2017), the company searched for its soul and moved away from a focus on utility (saving money) to deeper reasons for Airbnb to exist. Two words: “Belong Anywhere”. Just two words can change the whole meaning of staying or booking a place. When customers believe what your brand believes, all things being equal, they will likely choose you over a competitor with the same offerings.

2. Find your "enemy":

Another technique involves identifying an “enemy” to defeat. Travellers choose Airbnb because they feel part of the sharing economy movement, and believe tourism should benefit hosts and local communities. The enemy? Mass tourism.

3. Align your what (your offerings) with your why:

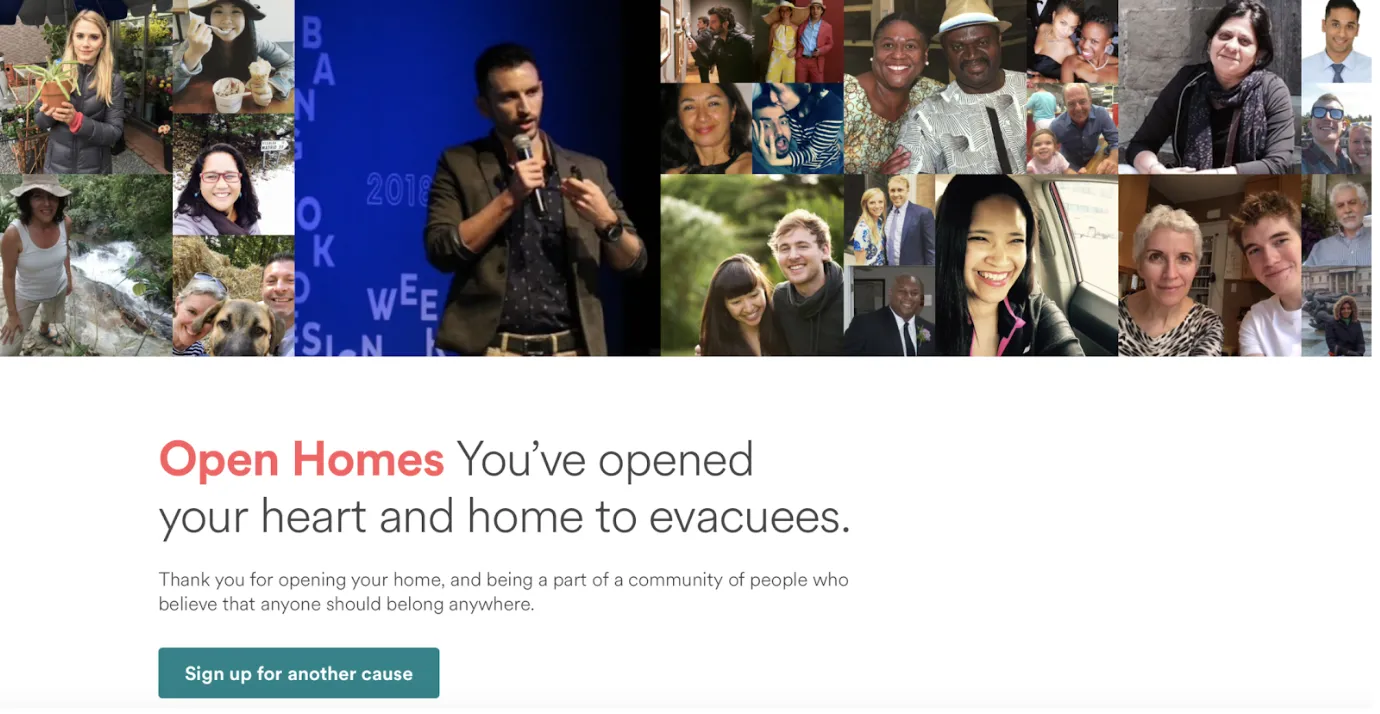

Finally, Airbnb launched the Social Impact Experiences (guided tours and experiences by nonprofit organisations that receive 100 percent of what travellers pay) and the Open Homes Program, which allows hosts to open their doors to refugees and displaced people.

Airbnb also knows that the way we communicate and shape the experience and the user journey, can transport people emotionally.

Make it immersive

Oliver Schlake notes “[…] the company figured out a way in 2008 to engage people in a storyline that starts online and then crosses to the real world (when a stranger shows up on your doorstep, suitcase in tow) […]. Something similar happens in video games, when players open a portal or enter a cave to see what happens next” (Robert H. Smith School of Business).

At the launch of Trips (which allows hosts to craft local experiences to travellers) Airbnb’s CEO talked about what’s behind the new product: the “Hero Journey”, a “story” of one main character going through a transformational journey.

And what is a journey without exploration and discovery?

Make it intriguing

In The Airbnb Story, Gallagher (2017) notes how the breadth and whimsy of the options offered makes scrolling through Airbnb’s listings an exercise in escapism. The exciting search of the most popular and unique homes is facilitated by infinite scrolling, an interaction technique that allows users to scroll through a massive amount of content with no finishing-line in sight..

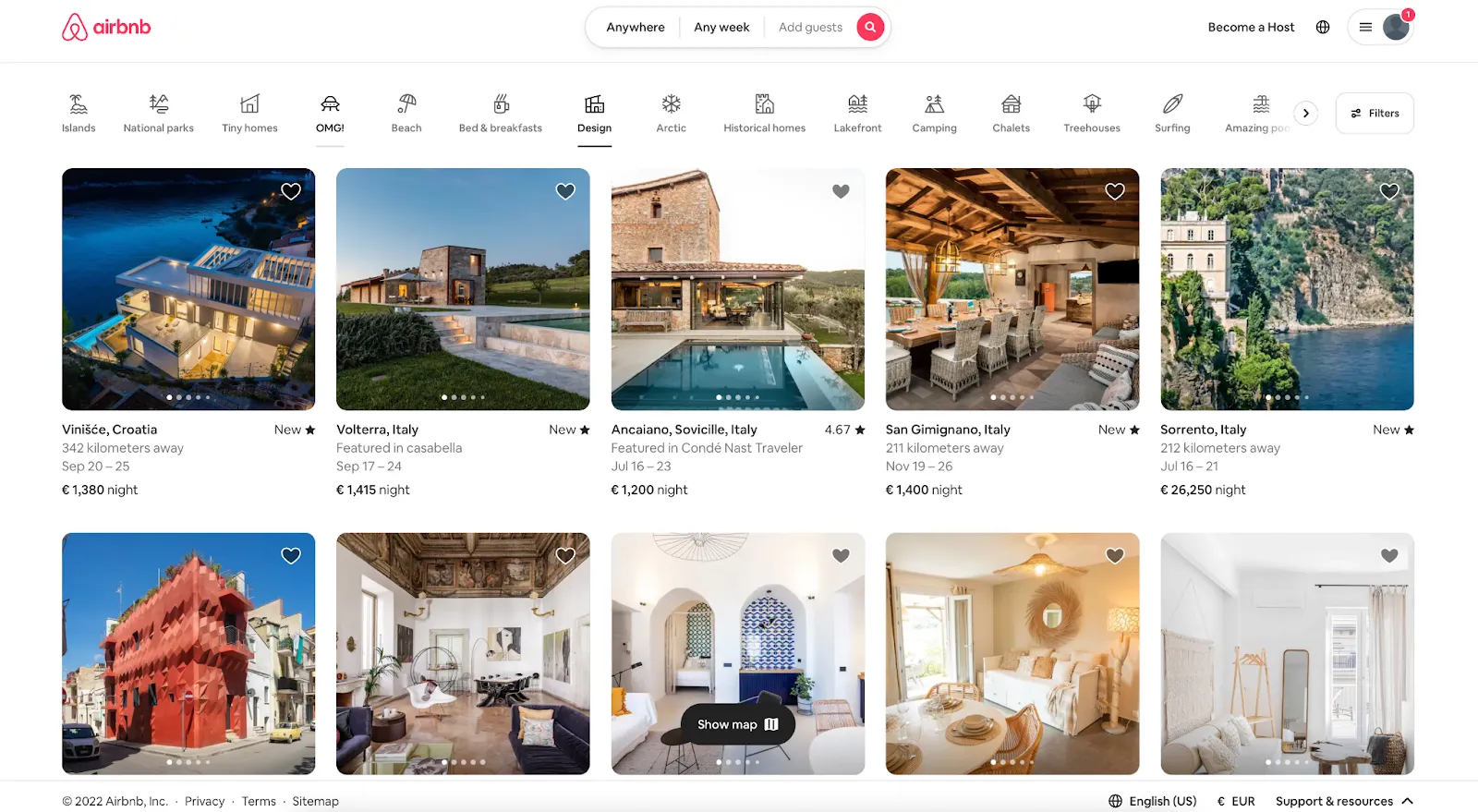

Another great example of the role of choice architecture in shaping our decisions is the most recent redesign of the search experience.

Brian Chesky, CEO of Airbnb, saw the need to disrupt the way of how people search for holiday homes:

“We’re in a hundred thousand cities. Very few people can think of typing in more than 20 places. So what happens? Everyone ends up going to the same places. Everyone goes to Vegas and Miami and New York and Paris and Rome and London.”

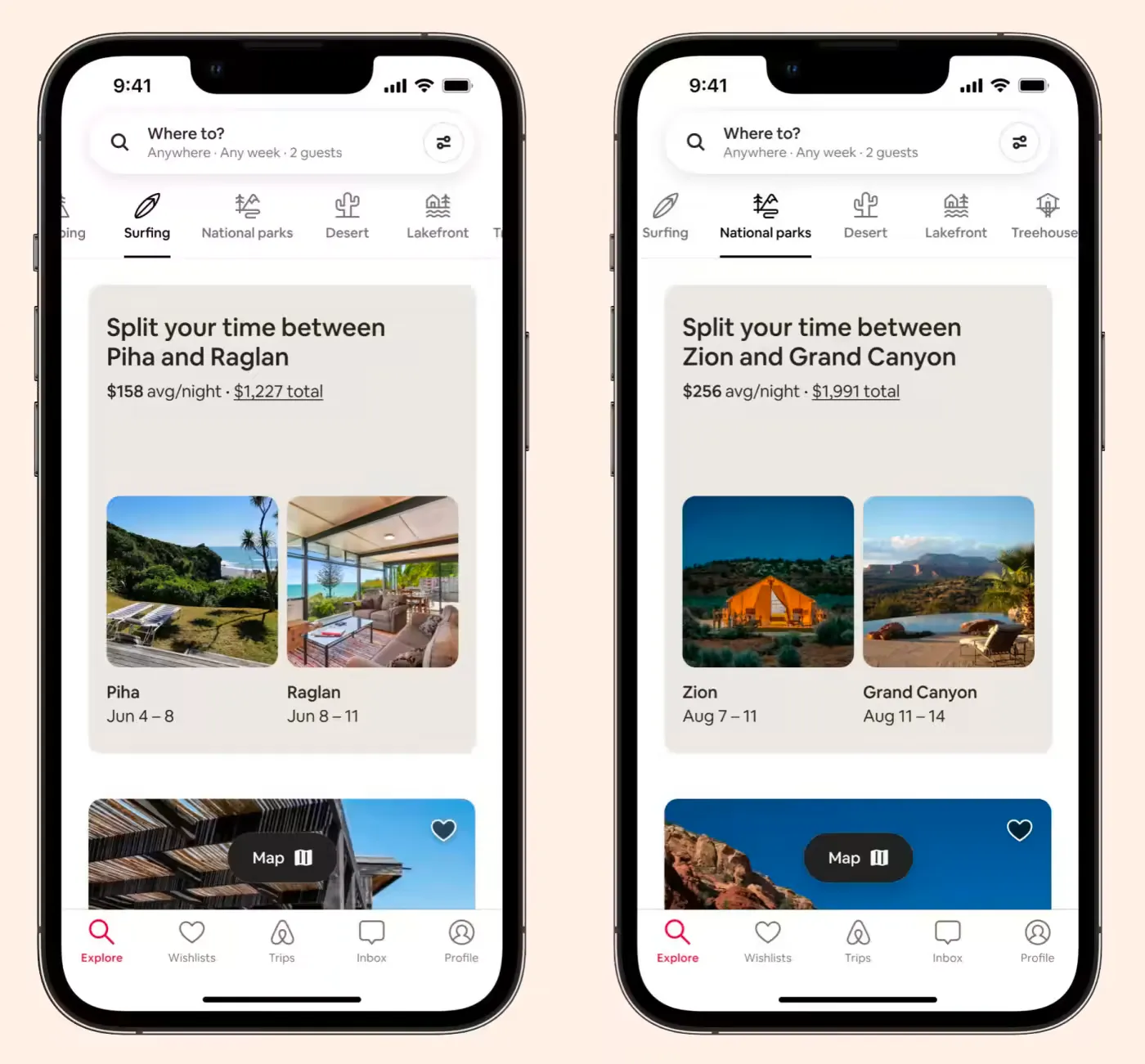

Tabs will filter approximately 4mn listings by functions — such as “surfing”, “skiing” and “camping” — as well as characteristics such as “houseboats”, “farms” and “castles”.

This will allow travellers to choose a home not by a destination. Raher, by the experience they are seeking.

The redesign includes “Split Stay”, a feature that suggests two locations that could be booked in tandem if no one single host can accommodate the full length of a stay.

This redesign, which represented the “biggest change to Airbnb in a decade”, redirects travellers to new destinations. And novelty is key in creating memorable experiences.

A sense of discovery and exploration should lead, at some point, to the other side of unpredictability: an unexpected event.

Make it unexpected

Unpredictability and delightful moments are introduced with two main vehicles. First, with marketing campaigns such as the “Night At” contest, which allows lucky guests to stay for only one night in unique accommodations (Lottery).

The second vehicle are the hosts themselves. While Airbnb has less control of the experience that hosts provide to their guests, they share tips and have created features (such as the Guidebooks by Hosts) to help them create guest-friendly homes and memorable experiences.

In addition to tips Airbnb has built an effective mastery phase to improve hosts skills., which we will deconstruct in part 2 of this article). For now, it’s worth noting that efforts put by the hosts into creating (at times surprisingly) positive experiences make hosts more likeable and thus foster the reciprocal behaviours discussed above.

Airbnb is without a doubt a successful product that cleverly combines behavioural science with UX and gameful design.

Stay tuned for part 2 where we’ll deconstruct how Airbnb designs for its hosts - and some opportunity points a Make it audit has identified.